Time & Empire traces the recurring design of dominance. Every age inherits an empire’s blueprint—military, economic, or digital—and repaints it as progress. These reflections follow the pattern through centuries, revealing how power learns to survive collapse by changing its name.

Archives › Time & Empire

The Invisible Tax: How Financial Repression Melts Government Debt

0

Imagine borrowing $100,000 when it is twice your annual salary–a crushing burden. Ten years later, you still owe $100,000, but you now earn $200,000 a year. Same debt on paper, but it now feels like pocket change. This is financial repression: the government’s secret weapon for escaping debt without anyone noticing.

Most people think governments pay off debt by raising taxes or cutting spending. But there’s a third way–one that’s invisible, legal, and devastatingly effective. It’s called financial repression, and once you understand how it works, you’ll see it everywhere.

What Is Financial Repression?

Before we dive into how this works, let’s be clear: financial repression is not a term I invented, nor is it some new conspiracy theory. It’s an established economic concept with a well-documented history.

The term “financial repression” was first coined in 1973 by Stanford economists Edward S. Shaw and Ronald I. McKinnon. They originally used it to describe policies in developing countries that restricted financial markets and held back economic growth.

However, the concept gained renewed attention after the 2008 financial crisis, when economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff — along with their colleague M. Belen Sbrancia — published groundbreaking research showing that financial repression wasn’t just a developing-world problem.

In their widely cited 2011 paper, “The Liquidation of Government Debt,” they demonstrated that advanced economies, including the United States, had used extensive financial repression after World War II to reduce massive debt burdens.

Reinhart defined it simply: “Financial repression occurs when governments implement policies to channel to themselves funds that in a deregulated market environment would go elsewhere.” In other words, it’s a way to force savers to lend money to the government at below-market rates.

The Three Players

To understand this economic sleight of hand, you need to know three characters:

- The Borrower: The Government (They owe trillions in bonds, which are basically IOUs promising to pay back a fixed amount plus interest)

- The Lender: You (Your savings account, your pension fund, your bank–anyone who holds government bonds or saves money)

- The Measuring Stick: The Dollar (The unit we use to measure everything–and the key to the whole trick)

Act I: The Setup (Locking in the Numbers)

Let’s say the government owes $10 trillion in bonds. They’ve promised to pay this back with 2% annual interest. Here’s what matters:

That $10 trillion is written in ink. It is fixed. Permanent. Unchangeable.

Meanwhile, the economy, let’s call it the GDP (Gross Domestic Product), is $20 trillion. That means the national debt is 50% of the economy’s total annual income. Think of it like owing $50,000 when your household earns $100,000 per year. Manageable, but heavy.

The government collects about 20% of GDP in taxes, so it is bringing in roughly $4 trillion per year. They use some of that to pay the interest on the debt (about $200 billion at 2% interest), and the rest goes to running the country.

So far, nothing unusual. But watch what happens next.

Act II: The Inflation (Shrinking the Ruler)

The government now allows, or quietly encourages, inflation to run at 5% per year.

Most people think of inflation as “things getting more expensive.” A loaf of bread goes from $2 to $4. Gas climbs from $3 to $6. But here is the better way to think about it:

Inflation does not make things more expensive. It makes money less valuable.

If bread doubles in price, it’s not because the bread got better or larger. It’s because each dollar now buys half as much. The measuring stick shrank.

At 5% inflation per year, prices roughly double every 14 years. After a decade and a half, that $2 loaf of bread costs $4. Your $50,000 car now costs $100,000. And your $3,000 monthly rent is now $6,000.

But remember: that government debt? Still $10 trillion. Frozen in time. Written in the old, valuable dollars.

Act III: The Economy Expands (The Missing Piece)

Here’s the part most explanations skip, and it’s the critical piece:

When prices double, something else doubles too:

The total size of the economy.

GDP isn’t a fixed number. It’s measured in dollars, the same dollars that are shrinking in value. So when inflation doubles, all prices and GDP double too.

- Before inflation: GDP was $20 trillion (the economy produced $20 trillion worth of goods and services)

- After inflation: GDP is now $40 trillion (the same amount of stuff, but measured in inflated dollars)

The economy didn’t actually get richer; it’s producing the same cars, bread, and services. But when you measure it in the new, weaker dollars, the number doubles.

Act IV: Tax Revenue Multiplies (The Government Gets Rich)

Now the magic happens. Governments collect taxes as a percentage of economic activity, roughly 20% of GDP. So:

- Before inflation: The government collected $4 trillion in taxes (20% of $20 trillion).

- After inflation: The government collects $8 trillion in taxes (20% of $40 trillion).

The government’s income just doubled, not because tax rates went up, but because they are taxing a “bigger” economy measured in inflated dollars. Meanwhile, workers’ salaries eventually rise to catch up with the cost of living. Individuals don’t feel much richer, but the government is now swimming in cash.

Act V: The Ratio Flips (The Debt Melts Away)

Now the government looks at its books:

- Income: $8 trillion per year (doubled thanks to inflation)

- Debt: Still $10 trillion (locked in from years ago)

Remember, at the beginning, the debt was 50% of GDP:

- Before: $10 trillion debt divided by $20 trillion GDP = 50%

- After: $10 trillion debt divided by $40 trillion GDP = 25%

The burden of the debt just got cut in half, not because the government paid anything back, but because the economy (measured in inflated dollars) got twice as big.

It’s like owing $50,000 when you earned $100,000 (a 50% burden), and then getting a raise to $200,000 while the debt stays at $50,000 (now only a 25% burden). You didn’t pay off a penny, but the weight of the debt evaporated.

With doubled tax revenue and a debt burden that’s now half as heavy, the government can easily service the interest payments, and even start paying down the principal if it wants. But they didn’t raise taxes. They didn’t cut spending. They just waited for inflation to do the work.

The Trap: Why Can’t Lenders Fight Back?

You might be thinking: “Wait, if I’m lending money and inflation is eating away at its value, shouldn’t I demand a higher interest rate?”

Absolutely. In a free market, if inflation is running at 5%, lenders would demand at least 5% interest just to break even, plus extra to make a real profit.

But under financial repression, the government rigs the game:

- They cap interest rates artificially low. Even though inflation is 5%, they keep bond rates at 2%. This means lenders are losing 3% of their real purchasing power each year.

- They force institutions to buy government debt. Banks, pension funds, and insurance companies are required by law to hold a certain percentage of “safe” government bonds, even though those bonds are guaranteed money losers in real terms.

- They limit your alternatives. Capital controls, regulations, and taxes make it difficult or illegal to move your money into inflation-beating investments like foreign assets, gold, or other hedges.

The result: Savers are trapped. Their money sits in accounts earning 2% while inflation runs at 5%. Every year, the real value of their savings shrinks by 3%, and that wealth quietly flows to the government, helping them pay off debt.

It’s a transfer of wealth from savers to the government, and most people never even notice it’s happening.

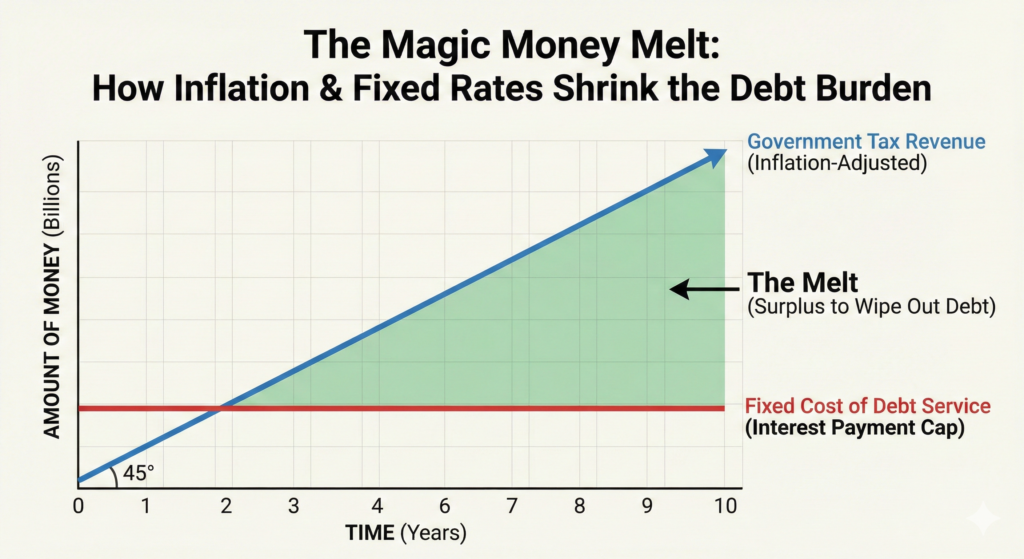

Seeing It: The “Jaws of Death” Graph

To visualize how this works, imagine a simple graph:

- The horizontal axis (bottom): Time, measured in years (0 to 10)

- The vertical axis (side): Dollar amounts

Now draw two lines:

- Blue line (Government Tax Revenue): Starts low and climbs steeply upward at a 45-degree angle as inflation doubles GDP and tax revenue over 9 years.

- Red line (Fixed Debt Payments): Stays completely flat because the debt amount and interest rate were locked in years ago.

The gap between these two lines, the space that widens like an alligator’s jaws, represents the financial breathing room the government gains.

At Year 0, tax revenue and debt payments are roughly balanced. By Year 9, tax revenue has doubled, but debt payments haven’t budged. The government now has massive surplus revenue to wipe out the debt burden, all without raising your tax rate by even 1%.

This widening gap is “the melt.” The debt did not disappear on paper, but its weight, its burden relative to the economy, evaporated.

It’s Not Theory–It Already Happened After World War II

This is not a hypothetical scenario. Financial repression has been used successfully by the United States and other advanced economies to eliminate massive debt burdens. The most striking example: America after World War II.

In 1946, the U.S. total debt-to-GDP ratio peaked at 119%. Today, we are in a worse position, with total debt exceeding 124% of GDP as of 2025. The war had been extraordinarily expensive, and the government owed more than the entire economy produced in a year.

By conventional wisdom, the nation faced decades of painful austerity, tax increases, and spending cuts to pay it down. But that’s not what happened. By 1974, the debt-to-GDP ratio had fallen to just 23%.

The debt burden essentially melted away. But here’s the key: the government didn’t actually pay off the debt. The nominal debt level stayed roughly the same. Instead, the economy grew massively in inflated dollars, making the old debt irrelevant.

How did they do it? Financial repression.

- Capped interest rates: From 1942 to 1951, the Federal Reserve agreed to cap interest rates on government bonds at 2.5% or lower, even as inflation ran higher. This created negative real interest rates, meaning savers lost purchasing power every year.

- Captive investors: Banks and financial institutions were required to hold government bonds. They had no choice but to accept below-market returns.

- Controlled inflation: Inflation was allowed to run moderately high during the 1940s through the 1970s. Real interest rates on government debt were negative about half the time between 1945 and 1980.

Research by Carmen Reinhart and M. Belen Sbrancia found that this “financial repression tax” saved the U.S. government between 1% and 2% of GDP per year during this period. Over 35 years, that added up to cumulative savings potentially as high as 70% of GDP, an enormous wealth transfer from savers to the government.

The same pattern played out across the developed world. The United Kingdom saw its debt-to-GDP ratio fall from 216% in 1945 to 138% by 1955. France, Italy, and Australia all used variations of the same playbook.

This wasn’t a secret conspiracy. It was deliberate policy. And it worked.

What to Watch For: Signs of Financial Repression Today

Given the current global debt situation, with U.S. debt exceeding 120% of GDP and many advanced economies facing similar burdens, it’s worth asking: Is financial repression happening again?

Here are the key indicators to watch. These are not predictions or alarmism, just factual markers that economists use to identify financial repression when it occurs:

- Negative real interest rates. This is the hallmark of financial repression. When the interest rate on government bonds or savings accounts is lower than the inflation rate, savers are losing purchasing power. For example, if Treasury yields are 3% but inflation is running at 4%, the real return is negative 1%. Track the difference between nominal rates and actual inflation, not the Fed’s 2% target, but real consumer price increases.

- Regulatory requirements are forcing institutions to hold government debt. Watch for increases in capital requirements that mandate banks, insurance companies, or pension funds hold a higher percentage of “safe” government bonds. These rules create a captive audience for government debt and suppress yields.

- Central bank bond purchases (Quantitative Easing). When central banks buy government bonds directly, they are effectively printing money to suppress interest rates. While often justified as “monetary stimulus,” it also conveniently keeps government borrowing costs low.

- Capital controls or restrictions on moving money abroad. If it becomes harder to move savings into foreign currencies, assets, or investments, that limits your escape routes from negative real returns. Watch for new reporting requirements, transaction limits, or taxes on foreign investments.

- Persistent inflation above central bank targets. If inflation consistently runs at 3-5% while the Federal Reserve claims it’s temporary or under control, that’s a sign. Especially watch the gap between official inflation statistics and your actual cost of living.

- Debt-to-GDP ratios are improving without austerity. If government debt ratios start declining, not because of spending cuts or major tax increases, but seemingly by magic, that’s often financial repression at work. The debt burden is being inflated away.

- Yield curve control or interest rate caps. If the central bank explicitly targets long-term interest rates (not just short-term rates), that’s a modern version of the 1940s policy. Japan has done this for years; watch for similar policies elsewhere.

As of early 2025, several of these indicators are flashing. Global debt levels are at or near post-WWII highs. Central banks have been active buyers of government debt. Real interest rates have been negative or near-zero for extended periods. These are facts, not speculation.

Whether this is full-scale financial repression is a matter of interpretation. But the tools are in place, the precedent exists, and the debt burden is enormous. It’s worth paying attention.

Why This Matters

Financial repression is quiet, invisible, and perfectly legal. Unlike a government default or a sudden tax hike, it doesn’t make the headlines. There is no big, dramatic moment when the government announces, “We are melting our debt with inflation.”

Instead, it unfolds slowly:

- Your savings account earns 2% while prices rise 5%

- Your salary goes up, but so does everything else, so you do not feel richer

- Government debt-to-GDP ratios magically improve without any painful cuts

- Politicians take credit for “fiscal responsibility” without actually doing anything

It’s the ultimate illusion: debt that disappears not through payment, but through time and inflation. The government borrows a luxury car’s worth of money and pays it back with bicycle money, all while following the rules.

And who pays the real cost? The savers. The retirees on fixed incomes. Anyone who trusted that a dollar saved today would still be worth a dollar tomorrow.

The FSJ Perspective: How to Stand Under a Falling Sky

At The Falling Skies Journal, we look at history not just to understand the past, but to shield ourselves from the future. The “Magic Money Melt” is not a glitch; it is a feature of the current sovereign debt cycle.

So, if the “Falling Sky” in this scenario is the slow devaluation of your labor and savings, how do you hold up an umbrella?

- Don’t Be the Lender: The primary victim of financial repression is the person holding cash or government bonds. In this regime, cash is not a store of value; it is a melting ice cube.

- Own “Hard” Assets: If the government is shrinking the dollar (the measuring stick), you want to own things that cannot be shrunk. Historically, this means real assets—real estate, commodities, productive businesses, or decentralized assets that have a hard supply cap (like Bitcoin). These assets tend to re-price higher as the dollar weakens.

- Debt Can Be a Tool: Just as the government uses inflation to melt their debt, you can use it to melt yours—provided that debt is fixed-rate and attached to a hard asset (like a fixed-rate mortgage on a home). You pay back the bank with the same “cheaper” dollars the government uses.

The Bottom Line: You cannot stop the repression, but you do not have to be its victim. The “invisible tax” is only voluntary for those who leave their wealth trapped in the system designed to melt it.